The Effects of Family of Origin on an Individual’s Attachment Preferences

Kourtney Hernandez, Katelyn Louder, Michael Kezele, Nate Richardson

SFL 290 – Brigham Young University

Professor Draper

Abstract

The family an individual is raised in can change their entire schema, perception, and trajectory of life. This study seeks to understand whether the size of an individual’s family plays an important role in their attachment preferences, whether they prefer closer ties with friends or family. In order to measure this 300+ participants were surveyed about their preferences between family and friends, how many siblings they had, and how they perceive their personal happiness. From the data we can infer that the larger the family, the more interconnected you will be. This report will discuss in greater depth the results and conclusions from the survey.

Introduction & Literature Review

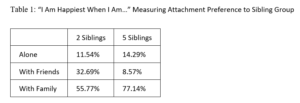

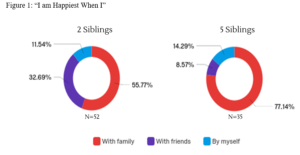

The concept of attachment preferences in emerging adults is an under-researched topic. Not many people have taken the time perform research in this area and it deserves to be studied more in depth. This contemporary issue will be studied to observe what causes emerging adults to choose to focus on certain relationships. Studying this subject would be beneficial to people and make society a better place as the research findings would give results as to what might predict close relationships with friends or family. Having this knowledge would be beneficial as we could figure out what drives people to have tightly knit family relationships (even if they have relocated or moved away from the family of origin). Also worth consideration is the individual who has gone down a different path in life and was never very close to their family, but has found amazing friends that they can trust. With the results, predictions could be made to see if the size of one’s family of origin will impact their relationship inclinations or not (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). The study hypothesis is that the size of the family of origin directly correlates with the attachment preferences (family or friends).

It was assumed that that when the research was completed it would help people everywhere in relationships. For example, maybe the results come to be that if one has a large family they are more likely to be close with friends and distanced from family. Knowing this as a parent would be beneficial as one would know that they need to work on relationships with children and making sure they know that they are all loved and wanted. On the other hand, maybe these research findings will show that those who have small families are very closely knit, but as a downside they do not get out often enough to interact and create relationships with classmates. This could help that same person know that they need to go to more school activities and involve themselves with children from class. It is important to complete this research to find how coming from a large or small family with have a significant impact on the relationships one has and who one has them with.

The current literature has taken more of a focus on romantic relationships’ effect on an individual rather than familial effect. Beyond even the study of familial effect on attachment preferences there have been little to no studies done on the role that family size plays as a variable in that equation. This lack of research leaves plenty of room for questions and very few answers. This study intends to infer the most we can from the available research but also discover the relationship or lack thereof. The hypothesis here observed is that the size of one’s family of origin directly correlates with their attachment preferences (i.e. if they feel a stronger connection to family versus friends). This study will be researching to find if the family of origin will have an impact on an individual’s relationships which in turn could cause a family (or husband and wife) to have the desire for a larger or smaller family because of the impacts it will have on their relationships.

One particular study by Tomo Umemura, Lenka Lacinov, Petr Macek and E S Kunnen focused on emerging adult attachment preferences between friends and romantic partners. In their research, they collected a sample of 379 participants and studied them at two separate points, the summer of 2013 and the following summer of 2014. Umemura et. al concluded from their research that those in the study who were involved in a romantic relationship either during both points of the study or had developed one in between, increased in their preferences for connection with their romantic partners as opposed to friends; whereas participants who were not involved in a romantic relationship at either point or in between, preferred friends over the idea of a romantic partner (Umemura, Lacinov, Macek, & Kunnen, 2017, p. 136-142). From this one may deduce that attachment preferences are not the same for all individuals and the relationships one has (or do not have) affects their personal attachment preferences. This study of interest could impact the study here performed because many college students (especially here at Brigham Young University) are dating and perhaps even looking for a spouse. It may simply depend on what stage of life one is in — that is where the strongest relationship will be. This is why it is important to perform a research study to find out where all of these current college students are at in their relationship attachments. An interesting observation made in current research is that:

“During adolescence and young adulthood, when remaining life time seems unlimited, information acquisition goals are relatively more prevalent compared with other life periods. People focus on gathering knowledge and information from diverse relationships and sources, which is achieved best in large networks with diverse relationship partners. After young adulthood and throughout the rest of adult life, when remaining life time is perceived as increasingly limited, emotion regulation goals become increasingly important. People emphasize emotional aspects of relationships and focus on close relationships, such as those with family members, with expected pleasant interactions that most likely satisfy emotion regulation goals” (Wrzus, Hnel, Wagner, & Neyer, 2013, p. 54).

This observation contributed to the understanding that emerging adults tend to veer away from family social networks because of the nature of the life period; unless they feel they have a large enough familial social network to have these needs met. Adding to the theory that family relationships are less important than friends in the emerging adulthood period of life is the theory presented by A. Graham that families and friend relationships are becoming “suffused” or there is an overlap between the two. Graham suggests that the current generation is engaging in such flexibility in distinction between relationships that friends may hold a higher esteem over family because they are considered to be an actual part of an individual’s family (Graham, 2008). This may be due to the nature of emerging adulthood, and that as one “enter[s] emerging adulthood, many individuals transition to a new home, separate and apart from their caregiver’s home and from siblings, which is likely to limit opportunities to interact and demonstrate supportive behaviors towards their siblings [and/or other family members]” (Portner, Riggs, 2016). From these studies it is observed that emerging adulthood may elicit specialized attachment preferences. With these theories in mind it will make more sense why perhaps the observed group of this study affiliates more with friends rather than family members.

Some final research conclusions that have aided the current conversation on the topic are the following. One study concluded that the larger the family the less the desire to move [away] and consequently the higher the preference for family attachment became (Chen & Yang, 2016). Researchers have also found that as family size and composition increased, personal depressive symptoms in the individuals tested, decreased. The two previous studies mentioned could support the theory that close familial relationships will be developed in larger families despite transition into emerging adulthood (Fuller-Iglesias, H., Webster, N. J., & Antonucci, T. C., 2015). Lastly, the socioemotional selectivity theory is an intriguing theory that really pinpoints the “why” behind the way people prefer different social attachments throughout different stages of life. The theory states that, “reduced rates of interaction in late life are viewed as the result of lifelong selection processes by which people strategically and adaptively cultivate their social networks to maximize social and emotional gains and minimize social and emotional risks” (Carstensen, 1992). From the study by Carstensen, one may visually see across the lifespan, an individual’s closeness, satisfaction, and interaction in their relationships is highly dependent on their age (Carstensen, 1992).

Method

The theory tested here, that attachment preference–to family versus friends–will be affected by family of origin size, will be difficult to correlate. A survey was created to highlight how people would act in specific situations, directing their response into either the category of family or friends. The survey easily determines family size, but determining who one turns to in life for connection is difficult to certify.

The population sampled was primarily emerging adults (age 18-25). Other ages were also sampled, but this survey will differentiate between ages from questions on age.

The sample primarily targeted Brigham Young University (BYU) students, but other random persons were surveyed as well. The study differentiated between students and non-students by a survey question. This allowed the comparison of students to non-students in addition to the primary sample of BYU students.

The survey was administered to approximately 100 BYU students and 200 non-BYU students, giving a total baseline of 300 participants. The survey was solicited to BYU students and others via social media. The online survey tool “Qualtrics” was used to administer the electronic self-survey (see appendix).

The survey was given to everyone and anyone. There was no discrimination on grounds of education, class, social status, or gender. Discrimination occurs inside of the survey based on age, BYU student status, and family of origin size.

These discriminating factors of the survey played a key role in finding data. The separating of persons into groups allowed one to see how much bias is coming from BYU students compared to non-BYU students. Family size showed if a person raised in a larger family of origin would prefer family relationships to other social relationships (coworkers, friends, etc.). Age helped sort the data on preference to family versus other social relationships, as the married/older persons were likely to be more bias toward family instead of other social relationships.

Some of the survey questions were positive, some were negative. For example, if a person tells their family about a negative event, they are typically comfortable or close to their family. If the individual lies about a negative event to family (or simply chooses not to share) but will tell friends, a preference is apparent for non-familial social relationships. Looking at who the sample shares negative events with helped measure attachment preferences.

The marital status question is included because it helps the observer to put into perspective the individual’s preferences; it is natural for married people to turn to a spouse or children, rather than friends.

The independent variables include: age, BYU student status, marital status, number of siblings, and the makeup of the family of origin. The dependent variables include: closeness to family and closeness to friends. The survey questions were scrutinized in an attempt to eliminate as many extraneous variables as we can. The student status was measured with a simple question “are you a BYU student? Yes/No”. The study measured the marital status with a question “what is your marital status? Single, Married, Divorced, Not Looking, Other”. The study measured number of siblings with a question “How many siblings do you have?” and the person will be able to fill in how many they have. The study measured closeness to family versus closeness to other social relationships with hypothetical questions asking whom they would turn to in common situations, the choices being between family and other social relationships. The survey questions employed several categories they could respond to i.e. roommates coworkers, friends, family, brothers and parents. This was to help them to relate to questions better, but the study is just looking at friends (non-familial social relationships) versus family.

The research design is descriptive research due to the fact that the population was random, and the study was merely finding and describing what is occurring in the respondent’s present unaltered situations.

From the survey results, inferential statistics were created. These have and will provide insight into the personal biases and preferences of the participants. Descriptive statistics were used from the survey results to show if there are any correlations between individuals attachment preferences and size of the family of origin…as well as additional factors that might play a role.

Results

Upon reviewing the data it is apparent that the size of one’s family does indeed affect an individual’s preference towards family or friends.

[Insert Figure 1 here and table 1 here]

The biggest difference found was between people with two or fewer siblings compared to their counterparts who had three or more siblings. The group with two or fewer siblings was more inclined to call or communicate with their families less often, spend more time with friends than family on the weekends, and be happier when with their friends.

Another interesting result found that those who had more siblings had a higher rate of parents who were still married compared to individuals with fewer siblings were more likely to have divorced parents.

The correlation between number of siblings and when one is most happiest (with friends or family) was found to be .17. Though this is not a strong correlation there is still a positive correlation that the more siblings one has the more they are attached to their family rather than the friends. The findings of the study, though minimal, confirm the thesis.

Discussion

In conclusion with the research question, on average the more siblings a person has, the more their affinity toward family instead of friends. This refutes the idea that the more siblings one has, the less likely they will want to spend time at home in a perhaps more chaotic environment. Individuals with large families (three or more siblings) prefer to spend the majority of the time with their family overall. That tends to be when they are happiest.

There is a great difference between family preferences when a family changes from having two children to having three children. It was seen that the larger the number of siblings a person had, the more they wanted to spend their time with family as opposed to friends.

The number of siblings positively correlated with the amount of time a person preferred to spend with their family as opposed to friends.

In summary, the more children a family has, the more knit together they will be. They will want to call home more often, they will be more likely to have deeper relationships with family members and maintain contact with them even when they do not live together.

Limitations

The survey was distributed via social media to increase the sample size and to gather a more representative sample. However, the online friend groups that the survey was distributed to did not necessarily provide a sample that represented the whole population. Additionally, the test did not account for: the health of the family relationships, individuals who do not have families but rather, grew up in orphanages or in the foster system, for individuals who suffer from any physical or mental disorders, or the effect that those disorders have on an individual’s ability to socialize. Furthermore this test did not account for external variables like schedule; work hours, volunteer hours, personal hours and the effects that that time has on utilizing relationships.

Initial predictions that a large number of respondents would be emerging adults, currently enrolled at Brigham Young University, an institution sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. This sample contained cultural views on the value of family, which have the potential to skew the results. Some respondents may have answer certain questions in favor of family because of cultural expectations. The study attempted to eliminate these trait errors by asking for honesty from the respondents, stating and protecting anonymity and drawing part of the sample from outside resources.

References

Carstensen, L. L. (1992). Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional

selectivity theory. Psychology and aging, 7(3), 331-338.

Chen, J., & Yang, H. (2016). Geographical mobility, income, life satisfaction and family size

preferences: An empirical study on rural households in Shaanxi and Henan Provinces in China. Social Indicators, 129(1), 277-290.

Fuller-Iglesias, H., Webster, N. J., & Antonucci, T. C. (2015). The complex nature of

family support across the life span: Implications for psychological well-being.

Developmental Psychology, 51(3), 277-288. doi:10.1037/a0038665

Graham, A. (2008). Flexibility, friendship, and family. Personal Relationships, 15(1), 1-16.

Martinson, V. K., Holman, T. B., Larson, J. H., & Jackson, J. B. (2010). The relationship

between coming to terms with family-of-origin difficulties and adult relationship satisfaction. American Journal of Family Therapy, 38(3), 207-217. doi:10.1080/01926180902961696

Portner, L.C. & Riggs, S.A. J Child Fam Stud (2016) 25: 1755.

doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0358-5

Umemura, T., Lacinov, L., Macek, P., & Kunnen, E. S. (2017). Longitudinal changes in emerging

adults attachment preferences for their mother, father, friends, and romantic partner: Focusing on the start and end of romantic relationships. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(1), 136-142.

Wrzus, C., Hnel, M., Wagner, J., & Neyer, F. J. (2013). Social network changes and life events

across the life span: A meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 139(1), 53-80.

Survey:

- Are you a current college student? Choose 1.

- Yes

- No

If yes, are you a currently enrolled as a student at Brigham Young University? Choose 1.

- Yes

- No

- What is your gender? Choose 1.

- Male

- Female

- Other

- How old are you? Choose 1.

- 18-20

- 21-24

- 25-30

- 30+

- Which of the following choices best represents your family of origin makeup: Choose 1.

- Single parent

- Blended family

- two parents

- divorced parents

- one parent widowed

- How many siblings do you have? Fill in the blank.

- Marital Status: Choose all that apply.

- Single

- Married

- Divorced

- Not looking

- Other

- I am happiest when I am: Choose 1.

- With family

- With friends

- By myself

- How do you choose to spend your weekends? Choose 1.

- In quiet solitude

- Outs in the world in social settings

- With family

- You are about to move to Montana, but hesitate leaving your home turf which is 300 miles away. Montana seems less expensive, will have better jobs and cleaner air. In this situation what would make you hesitate? Drag the scale to match your preference.

- distance from my family

- distance from my friends

- Which type of schooling do you prefer? Choose 1.

- Public school

- Private school

- Home school

- You were caught cheating on a test. Who do you confide in first? Choose 1.

- Coworkers

- Roommates

- Parents

- Siblings

- Friend

- No one

- You just got engaged to be married and are so excited! Who do you share this wonderful news with first? Choose 1.

- Coworkers

- Roommates

- Parents

- Siblings

- Friends

- When you moved out for this first time away from your family, how often did you contact them? Choose 1.

- Once a week

- Every day

- Once a month

- On holidays/reunions

- Never

- Which factor do you consider most important in categorizing someone as a close friend? Choose 1-2.

-Trusting relationship

-Frequent contact

-Proximity

-Similarities

-Relative

- Do you feel you lean more towards family relations or friendships to help you feel happy on a daily basis? Drag the scale to match your preference.

-Family gives me all my happiness ——————-Both sources———————-Friends give me all my happiness. (slider scale)

- Rate your happiness from 1 to 10. Drag the scale to match your preference.

1 (very unhappy)——————-5(typically happy)———————10(always happy)

- How often do you feel happy? Choose 1.

- Very often

- Often

- Seldom

- Never

Figure 1: “I am Happiest When I”